Princeton University Prof. Says Codex Mashhad 'Valuable' for Studying Quran History

Michael Cook sent an exclusive message about the Codex in which he touched upon the importance of this ancient manuscript.

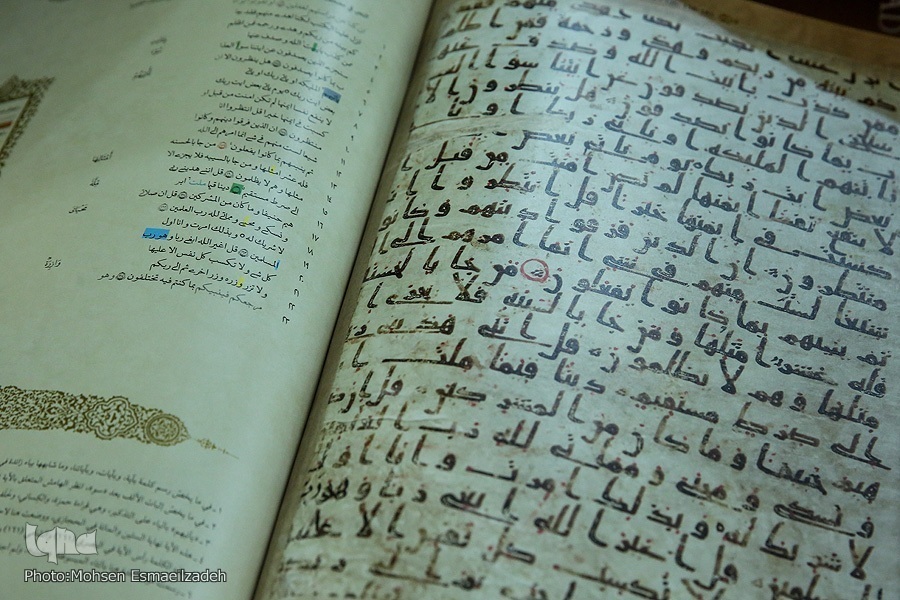

Dating Back to the first century after Hijra (7th century AD), the codex is in Hijazi script — the collective name for a number of early Arabic scripts that developed in the Hejaz region of Arabia.

What follows is Cook's message:

The early history of the Qurʾānic text is a field that has seen striking progress in recent decades, despite the fact that only a limited number of really early copies of the Qurʾān, or substantial parts of it, survive today. One of them is a codex large parts of which are found in two manuscripts preserved in the library of the sanctuary in Mashhad. Radio-carbon dating indicates that this codex could be from as early as the second half of the first/seventh century, and palaeographical study supports such a dating. The text is largely identical with the form of the standard text that our sources associate with Medina, but occasionally it agrees instead with readings tied to other regions. By contrast, the division of the text into verses diverges from those of all the various regional traditions known to us. Surprisingly, at three points the codex appears to preserve older readings where those of the standard text were on one account introduced by Ḥajjāj (d. 95/714), the governor of Iraq. For all these reasons and more, making such a codex available to scholars is in itself a valuable service to the study of the history of the Qurʾān.

But this codex is not just early, it is also very intriguing. Like almost all our witnesses to the early Qurʾān, it contains the text more or less as standardized in the mid-seventh century, and with the Sūras in the standard order. Yet Karimi-Nia’s careful study shows beyond doubt that the order of the Sūras was reworked at some point in the later history of the codex by a drastic process of cutting and pasting. Originally the Sūras were in a quite different order, one identical with that described in our sources for a version of the text that we no longer possess, but know to have antedated the standardization. This leads to yet another puzzle: this lost version was associated with the city of Kūfa (and Ibn Masʿūd) in Iraq, whereas the version of the standard text behind the Codex Mashhad is Medinese. Just what circumstances gave rise to this strange hybrid — almost though not quite unique — is a fascinating question. Whatever the answer, this codex is a key exhibit in the little-known history of the relationship between the standard text and those it replaced.

Read More:

According to Quran researcher and translator Morteza Kariminia, the textual characteristics of this codex, including custom features, spelling features, variations in readings, and the arrangement of surahs, along with extensive Carbon 14 testing, reveals that the primary portion of this version dates back to the first century.

This edition includes explanations and an annotated introduction in both Arabic and English languages, presented in facsimile printing to faithfully replicate the original, he added.

Codex Mashhad was unveiled in a ceremony in Mashhad in late November. The 252-page copy contains 95 percent of the text of the Holy Book.

It was written on parchment measuring 35 by 50 centimeters either in Medina or Kufa and was later taken to Khorasan (northeast Iran).

Then in the late 5th Hijri century, the owner endowed the copy to the holy shrine of Imam Reza (AS).

Source: Agencies