Researcher Delves into Biblical Echoes in Quran Interpretations of Ibn Barraǧān and Al-Biqāʿī

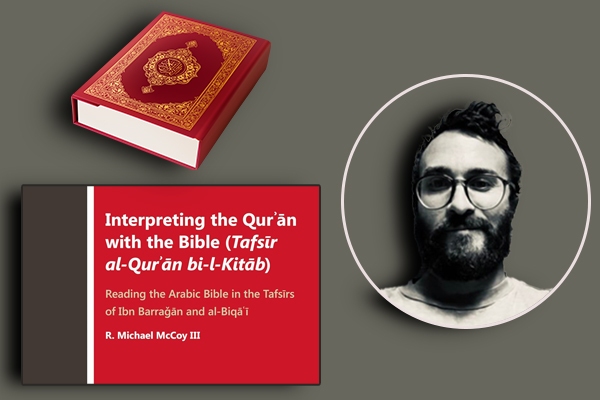

Roy Michael McCoy, a researcher and author, provided insights about his recent research while addressing an online lecture hosted by the Inekas Institute in early September 2024.

McCoy’s remarks were largely drawn from his book, Tafsīr al-Quran bi-l-Kitāb: Reading the Arabic Bible in the Tafsīrs of Ibn Barraǧān and al-Biqāʿī, which examines how two influential Muslim exegetes, Ibn Barraǧān of medieval al-Andalus and Burhān al-Dīn al-Biqāʿī of Mamluk-era Syria and Egypt, used Jewish and Christian scriptures in their Quranic exegesis.

Through his lecture, McCoy pointed to the subtle yet critical differences in their hermeneutical goals and methodologies—differences shaped by time, geography, and intellectual environments.

Both Ibn Barraǧān and al-Biqāʿī employ “biblical material to explain and amplify certain passages in the Quran,” McCoy explained, noting that, however, their motivations and interpretive frameworks diverge.

The interpretive practice known as tafsīr al-Quran bi-l-Kitāb—literally, interpreting the Quran through the Book, meaning the Bible—has roots in Islamic history that are often neglected in modern discourses. McCoy’s work traces this method through the intellectual contributions of Ibn Barraǧān (d. 536/1141) and al-Biqāʿī (d. 885/1480).

Ibn Barraǧān, who lived in the multicultural milieu of 12th-century al-Andalus, was known for his integration of scriptural reasoning with Sufi mysticism. His use of biblical references—particularly the Torah and the Gospels—was rooted in a quest for thematic and symbolic resonance between the Quran and the earlier scriptures, explained the researcher.

“Ibn Barraǧān espoused a particular form of Quranic interpretation, known as iʿtibār, or contemplative crossover,” he said, adding that it was about uncovering divine order and metaphysical patterns that link scripture to scripture.

For Ibn Barraǧān, interpreting the Quran through biblical texts was not an act of polemics but of taʾammul—deep contemplation. His tafsīr employed quotation from the Bible to highlight what he believed were hidden harmonies, according to the researcher.

One of the most compelling examples McCoy shared from Ibn Barraǧān’s tafsīr was the story of Adam and Eve. In his interpretation of Quranic verses such as Surah Al-A’raf (7:19–25), Ibn Barraǧān drew attention to the two trees in the Garden of Eden—the Tree of Life and the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil—as they appear in Genesis. These, he argued, could be symbolically linked to divine commandments and prohibitions in the Quran.

“Thematic harmony provides the most explicit examples of hermeneutical correlation between Ibn Barajan's methods of Quranic and biblical exegesis,” he said.

Read More:

By contrast, Burhān al-Dīn al-Biqāʿī, who lived in 15th-century Damascus and later in Cairo, worked within a much more polemical framework. As McCoy emphasized, al-Biqāʿī’s engagement with biblical texts was primarily theological. He sought to prove the legitimacy of Prophet Muhammad’s (PBUH) mission using the Bible—especially through prophecies and typological parallels.

Seeing the Bible as a reservoir of proofs, Al-Biqāʿī aimed to demonstrate that the Quran and the prophethood of Muhammad (PBUH) are not only consistent with earlier divine texts, but anticipated by it.

While Ibn Barraǧān turned to the Bible to uncover deeper spiritual resonances, al-Biqāʿī employed it as an argumentative tool, McCoy said, adding, his Naẓm al-Durar, a well-known Quranic commentary, frequently cites the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament to support Islamic theology.

Understanding the divergence between these two exegetes requires a look into their respective contexts. Ibn Barraǧān thrived in a period where Muslims, Jews, and Christians coexisted intellectually, especially in cities like Seville. The Andalusi atmosphere facilitated a spiritual curiosity and openness to intertextual interpretation, said McCoy.

In contrast, al-Biqāʿī operated in a very different environment where apologetics and polemics were central concerns in the Mamluk era, especially in Damascus and Cairo.

Read More:

Both scholars, however, shared one crucial hermeneutical belief: the internal coherence of the Quran. Each believed that the Quran possessed a divinely ordained structure, a belief that shaped how they read not only the Islamic scripture but also the biblical texts in relation to it, McCoy pointed out.

Ibn Barraǧān embraced the doctrine of nazm al-Quran, the view that the Quran is divinely ordered, with each sūrah and āyah fitting into an architecture. This conviction led him to seek deeper unity not only within the Quran but between the Quran and the Bible, said the researcher.

Meanwhile, al-Biqāʿī employed the theory of munāsibāt which held that each verse and chapter of the Quran was meaningfully connected to what precedes and follows it, McCoy said, adding that al-Biqāʿī sums up this science in one statement: “the more hidden a connection is, the more powerful it is once you see it.”

This theory “guides al-Biqāʿī exegesis at almost every turn,” notes the author.

Both exegetes believed that the Quranic text is not just a collection of verses, but a divinely ordered discourse where every verse and surah holds thematic and textual relationships with the rest of the scripture, noted McCoy.

Read More:

Ibn Barrajan believed that God had arranged the Quran in a meaningful order, and through iʿtibār (contemplative cross-over) we can uncover a higher coherence, a divine architecture of meanings, said the researcher.

Ibn Barraǧān’s analysis of the Adam and Eve narrative draws on various Quranic passages—from Surah al-Baqarah, Surah al-Aʿrāf, and Surah Ṭāhā—to construct a theologically rich interpretation, which he deepens through reference to the Biblical Genesis account. He interprets elements from both texts, such as clothing imagery, as symbolic of spiritual states. His approach is comparative, aiming to reveal underlying patterns of divine instruction.

“For Ibn Barajan, the Qur'an's coherence extends beyond its own structure, linking it with earlier divine revelations,” noted the researcher.

Al-Biqāʿī’s approach centered on establishing thematic and textual coherence within the Quran through his principle of munāsibāt. He analyzed seemingly disjointed verses to reveal their internal consistency and narrative progression, according to McCoy.

Al-Biqāʿī’s method also extended to drawing parallels between the Quran and earlier scriptures, such as the Torah and the Gospels, viewing these connections as both literary features and signs of a unified divine message across Abrahamic traditions, said the author.

Read More:

“Al-Biqāʿī builds his interpretive method around the concept of munasibat, connections where it seeks to uncover the subtle links between Quranic verses and chapters. His approach not only explains the internal coherence of the Quran, but also forges links between the Quran and earlier scriptures, Torah and the Gospels,” he said.

Al-Biqāʿī extensively uses biblical texts, particularly from Deuteronomy and the Gospels, to amplify the meaning of the Quran, noted the researcher, adding that his cross-scriptural engagement “serves both as an interpretive tool and a theological argument, especially for the finality of Muhammad's (PBUH) prelude.”

“Al-Biqāʿī also emphasizes theological continuity across scriptures, constructing a narrative that shows how earlier texts, particularly biblical ones, foretold Muhammad's (PBUH) coming. His use of biblical material serves to link Muhammad's message with that of previous prophets, creating a cohesive theological narrative,” noted McCoy.

“Finally, both Ibn Barraǧān and Al-Biqāʿī demonstrate a commitment to harmonizing the Quran with earlier scriptures. While Ibn Barraǧān emphasizes nazm as the primary tool for revealing Quranic coherence, Al-Biqāʿī applies munasibat to uncover interrelationships within the Quran and between the Quran and previous texts,” he said in concluding remarks, adding, “By incorporating biblical texts into their interpretations, both scholars offer a valuable contribution to Muslim exegetical tradition, especially in their efforts to connect the Abrahamic scriptures in a coherent theological framework.”

Please note that the content reflects the views of the scholar and does not represent the views of the International Quran News Agency.

Reporting by Mohammad Ali Haqshenas