7th Century Quran Manuscript Goes on View in Birmingham

Many were overwhelmed by the experience.

“Thank God I can attend this exhibition in person,” one visitor wrote in a message left on the noticeboard in the exhibition room. “Please keep struggling to find another piece of the whole Quran,” wrote another.

The scholar who identified some of the earliest surviving parts of a copy of the Quran in the world – two leaves of parchment which may have been made in the seventh century in the lifetime of the Prophet Muhammad [PBUH] – in a volume in Birmingham university library, is slightly baffled by the emotional reaction of many to her discovery.

“I prefer to stay among my books and away from people,” Alba Fedeli, the Italian scholar who knew at a glance the significance of the leaves, said. “The books are not so difficult.”

Experts have already been arguing about the significance of the find – whether it pre-dates the compilation of the authorized complete text of the Quran or pushes that back to an earlier date than previously believed. Many of the theories will be thrashed out at an international conference at the university later this month.

Sue Worrall, director of special collections at the university, said scholars and institutions from all over the world had been in touch since the discovery.

Fedeli is modestly dismissive of the scale of her discovery. It was obvious, she said, that the beautiful script was seventh century, not the similar but clearly – to a scholar who has now been studying the earliest Quran texts for 15 years – ninth century script of the other leaves.

To the untrained eye, the two look almost identical, but Fedeli spotted the difference online and when she actually handled the manuscript, knew exactly where she had seen more of the same handwriting, in leaves in the collection of the French national library in Paris, which came from one of the oldest mosques in the world, in Cairo.

The edges of the Birmingham leaves have been damaged, but almost all the text is preserved and the parchment still milky white. Radio carbon dating at Oxford University came back with a date for the parchment – with 95% certainty – of between AD568 and AD645.

Muhammad [PBUH] is generally agreed to have lived between AD570 and AD632. His teachings and revelations were initially passed on orally, before being written down on stone, clay, the shoulder blades of camels, and parchment – precious material, expensive to prepare from the skins of goats or sheep. After his death, the earliest written versions were collected and compiled into an authorized text. The Birmingham verses, though written in an abbreviated form, are very close to a modern text, confirming the belief of devout Muslims that the words of the prophet have been passed on unchanged for 1,400 years.

The carbon dating gives us only a period, not a year, we cannot say that this is the earliest Quran fragment in the world, only that it is very early - and interesting,” Fedeli said.

The Birmingham leaves came into the collection through a remarkable man, Alphonse Mingana, a former Chaldean priest who went on to marry a Norwegian student he met in Birmingham. He was funded by the Quaker industrialist Edward Cadbury to go on three great manuscript collecting expeditions across the Middle East in the 1920s. Cadbury had a vision of creating in Birmingham a world class theological collection, with Jewish, Christian and Islamic objects and manuscripts.

The Paris leaves are known to have come from an ancient Cairo mosque, but Fedeli, who has studied Mingana’s accounts and journals, believes he acquired the Birmingham leaves separately, with the later leaves, through a dealer in Holland.

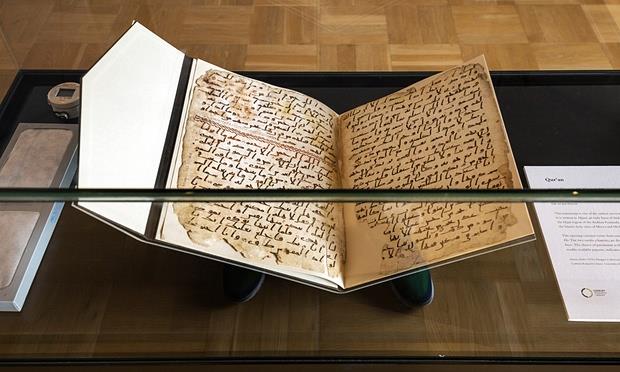

The seventh century leaves have now been conserved and bound separately in a traditional Islamic-style brown leather binding.

Muslim students and security officers at the university have volunteered to guard the manuscript and guide the public through the weeks of the exhibition: “It is a wonderful experience to spend time with this manuscript, I am really enjoying it,” Neelam Hussain, a postgraduate researcher on Arabic manuscripts, said.

Source: The Guardian