Ancient Leather Scrolls: A Pillar of Quranic Calligraphy Tradition in Tunisia

These artifacts, dating back to the early centuries of Islam, are considered a foundational reference for the study of Quranic calligraphy before the discovery of the Sana’a manuscripts in Yemen.

According to Al-Furqan Islamic Heritage Foundation, prior to the Sana’a findings, the Kairouan collection was regarded as the principal resource for scholars examining early Islamic bookmaking and manuscript arts. French Orientalist Georges Marçais and archaeologist Louis Poinssot conducted extensive research on these manuscripts. Their work helped document and identify the most significant artistic characteristics of the Kairouan codices, although their studies were mostly independent of the Quranic manuscripts housed in the library.

Further insights have come from reviewing historic records and uncirculated documents, such as early reports on the Kairouan manuscripts and critical editions of treatises like al-Taysīr fī Ṣināʿat al-Tasfīr (Facilitating the Craft of Bookbinding) by Shaykh Bakr ibn Ibrahim al-Ishbīlī. This work offers a detailed look at the various stages of leather production, along with technical and artistic terminology used in the craft.

The Rise of Leather Craft in Medieval Africa

Leather production in Africa flourished during the 10th and 11th centuries CE. Lavishly decorated Kairouani saddles, adorned with silver and silk, were among the luxury exports to European markets. Parchment manufacturing also gained prominence, with nearly all Quranic manuscripts and registers in North Africa produced on animal skins.

Andalusian scholars are believed to have adopted bookmaking techniques from North African artisans. During this period, Africa emerged as a central hub for manuscript production, exporting its goods to the East and Al-Andalus (Muslim Spain). Historical records indicate that African traders imported raw materials such as saffron (used for red dyeing), ammonia (for whitening leather), and silk (for fabric production) from Eastern regions, including India. Some premium leather was also sourced from Yemen.

Read More:

This flourishing trade and craftsmanship paved the way for the growth of Quranic transcription in North Africa. Calligraphers increasingly turned to the profession, producing highly elaborate works. One of the most well-known among them was Ahmad ibn Ali al-Warraq, who personally transcribed, vocalized, illuminated, and bound a complete Quran for an African prince. The endowment document for that copy states: "This Quran was copied, vocalized, illuminated, and bound by Ali ibn Ahmad al-Warraq in the year 410 AH / 1020 CE."

Discovery and Preservation of the Kairouan Scrolls

The rare Kairouan scrolls were discovered in a small room within the Great Mosque of Kairouan in the early 20th century. Initially kept at the Bardo Museum in Tunis, a substantial portion of the collection was transferred in 1985 to the Center for the Study of Islamic Civilization and Art. Today, selected scrolls are housed in the Bardo National Museum, Raqqada Museum, and Monastir Museum.

The manuscripts are categorized into two major groups:

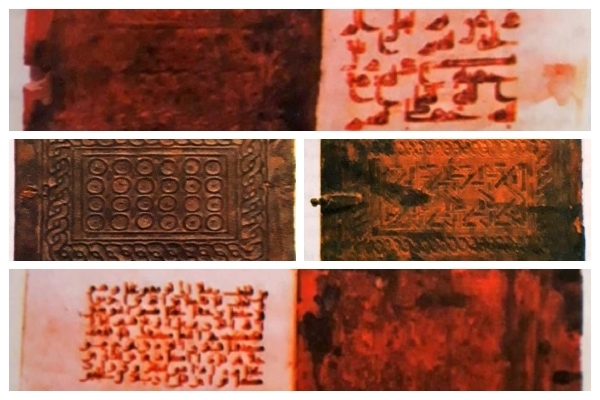

Group One includes scrolls of rectangular pieces ranging from 6 to 27 cm in length and 10.5 to 38 cm in width, typically with the length being two-thirds of the width. These manuscripts, dating from the mid-9th to mid-11th century CE, often feature olive wood boards and are thought to have been exclusively used for Quranic codices. However, records from 1556 CE indicate some were used for jurisprudential and Hadith compilations. These manuscripts were stored in chest-like wooden bindings that locked on three sides. Each chest could hold between 44 and 140 pages, with gatherings sewn together using colored silk threads. Metal locks—crafted from iron, brass, and occasionally silver—secured the pages. The decorations often featured intertwined circular designs, woven or geometric border motifs, and delicate ornamentation.

Read More:

Group Two represents later manuscripts with smaller dimensions, ranging from 12 to 22.4 cm in width and 15.4 to 21 cm in length. These were not encased in wooden covers but were bound using feltboard and secured with nails and thread rather than locks. The outer covering was made of a single piece of leather, while the interior lining used leather or fabric. This group is noted for simpler ornamentation but improved craftsmanship.

Dating and Classification of the Scrolls

Based on technical features and historical documentation, the collection has been divided into five chronological categories:

First Collection (9th century CE): Comprising 51 manuscripts with rectangular pages, these early examples feature chain and loop decorations on the bindings. Margins include parallel braids or rosettes, and the spines are often adorned with vertical lines. One manuscript, endowed to the Great Mosque of Damascus in 270 AH / 883–884 CE, provides a clear historical anchor.

Second Collection (10th century CE): Includes 18 manuscripts influenced by Italian design but distinguished by intricate decorative borders, circular patterns, and knot motifs. One volume was endowed in Jumada al-Thani 378 AH / September–October 988 CE, indicating its creation in the 10th century.

Read More:

Third Collection (Late 10th to early 11th century CE): Contains 45 manuscripts, some influenced by French styles, showcasing complex and rich ornamentation such as pear-shaped or diamond motifs, and interwoven knots. For the first time, inscriptions appear within circular medallions. These designs correspond to decorations found in Kairouan tombs from the same era.

Fourth Collection (contemporary with the third): Comprises nine scrolls with simpler thread-based decorations, limited to borders and foliate motifs. Although less elaborate, they represent a stylistic continuation of the third group.

Fifth Collection (12th–13th century CE): This final group is the smallest but stands out for its refined craftsmanship and focus on corner and front-cover embellishments. These features bear a strong resemblance to manuscripts housed at the Ibn Yūsuf School in Marrakesh. One scroll is dated to Rajab 654 AH / August 1256 CE.

To be continued…

4266744